焼き物の町 多治見で茶道のあれこれ ~焼き物・人・茶室~ 後編

たじみDMO(一般社団法人 多治見市観光協会)では、合同会社Mimir(小名田町1-3-4)に委託し、多治見を紹介するコラム(Discover TAJIMI 英語版・日本語版)を執筆していただいています。今年度は2つのテーマで配信される予定ですが、1つ目のテーマ「茶道」についてのコラム後編が完成したのでご紹介します。

英訳の詳細はこちらをご覧ください。

前編はこちら

陶芸家の視点から

THE POTTER’S PERSPECTIVE

前回のパート1では、日本の伝統的な文化である茶道についてお話しました。そこでは愛する多治見市を訪れ、茶道を個々に体験する方法について紹介しました。今回は2人の素晴らしい陶芸家の目を通して、茶道の本質を探っていきます。今回は物語にフォーカスし、茶道の中心である茶碗に隠された最もらしい物語に迫っていきます。それはこの儀式の核心を突き、その形の中には、ベールをはがされるのを待っているかのような物語があるのです。

In the initial segment of this piece, I shared insights about the enchanting tea ceremony, a time-honored cultural treasure of Japan. In that previous installment, we delved into the ways one can personally experience this tradition during a visit to our beloved Gifu Prefecture. Now, we embark on a fresh exploration, shifting our gaze to the ceremony’s essence through the eyes of two gifted potters. This time, our focal point is the narrative, as we unravel the compelling story concealed within the heart of the ceremony—the teabowl. It is the very core of this ritual, and within its form lies a tale waiting to be unveiled.

柴田育彦さん ―茶道といえば‟毒”という言葉が頭に浮かぶ

IKUHIKO SHIBATA: “WHEN I THINK OF THE TEA CEREMONY THE WORD ‘POISON’ KEEPS POPPING UP IN MY MIND”

陶芸家・柴田育彦さんのアトリエの片隅にひっそりと佇む茶室で、そのひとときをご一緒させていただく機会に恵まれました。 そこには、柴田さんの職人技とこだわりが詰まった茶器がずらりと並んでいます。

「私はまだ茶道の初心者ですが茶道について言えば、内戦に明け暮れていた戦国時代の武士たちに、お茶は会話の場を提供していたと思います。 狭い茶室で敵味方の区別なく会って交渉したのでしょうね。 気まずいような微妙な状況だから、お茶会のさまざまな道具が役に立ったのではと想像します」

As a devoted practitioner of the tea ceremony, Potter Ikuhiko Shibata finds profound significance in tracing its origins. For him, this exploration serves as a wellspring of inspiration, infusing his artistic creations with a profound depth of meaning and an unparalleled authenticity. I was privileged to receive an invitation to share a moment with Shibata in his unassuming tearoom, nestled in the corner of his studio. There, he had thoughtfully curated an array of tea utensils, each a product of his own craftsmanship and devotion.

“I am still a beginner student of the tea ceremony. There are so many things in Sado (the tea ceremony) to memorise. It’s overwhelming, but I have many impressions and feelings about this culture. I believe that o-cha (the tea ceremony) provided the samurai with an environment for conversation back in the times when our country was engulfed in a civil war. I imagine they met in some small tea room with allies as well as enemies to negotiate. It’s an awkward situation, and so the various tools of the ocha-kai (tea party) came in handy.

「『この茶碗、誠に立派でしょう!これは素晴らしい陶芸家が作ったもので、ちょっとご紹介しましょう』と、主人がその茶碗の話なんかを始めたり……」と柴田さんは続けます。

「主人は『有名な職人が手掛けたこの茶杓を手に取ってご覧ください。素晴らしい才能でしょう!それから水差しはいかがでしょう。そうそう高名な僧侶が書いた書の掛軸も素晴らしいですよ』……茶室ではこんな感じに話していたのでしょうね。これは、危険な時代に親しみやすい雰囲気を作り出す方法だったと思います。 茶室は平和な場所です。部屋の入り口(躙り口)は小さいので、剣を抜いて駆け入ることはできません。戦いに必要な武器は外に置いて入るようになっていました」と柴田さんは茶道について話し始めました。

「もう一つは茶道のそのものの形ですよね。ご存じのようにゲストは抹茶茶碗を受け取ると、飲む前に茶碗を回しますよね。例えば、戦国時代でホスト(亭主)はゲストに毒を盛るつもりだとしましょう。秘密裏に椀の縁のゲストに向いた部分に毒を塗って、ぐいっと飲むように勧めるでしょう。 椀を回すという作法は、そんな場合も考えてゲストにどこから飲むかを選ばせるためにできたかもしれません」

「同じ意味合いだと思うんですが、ホスト(亭主)は釜(鉄瓶)から柄杓(竹の柄杓)ですくった水の半分を抹茶碗に注ぎ、柄杓に残った半分は釜に返します。 釜に返すということはホストも同じ水を飲むということで、これは客に毒を盛ってないというもうひとつの保証を見せるためだと思っています」

“Imagine, for example, a host, a feudal lord, showing a chawan to his guest:” ‘This teabowl, it’s marvellous! It’s made by a great master; let me tell you about him’, and the host tells the story of that tea bowl.” “Or,” master Shibata continues, “the lord might say, ‘take this chashaku spoon; it’s made by this famous artisan. He’s such a gifted man.’ “Or, maybe it was the mizusashi (cold water container) or a kakejiku hanging scroll adorned with calligraphy by some famous monk.”

“In spite of the tiny world of the tearoom they were sitting in,” he continues, “there were a number of ice-breaking topics to bring up to lighten up the mood in a high-stakes meeting in the midst of war. This was a way to create a friendly atmosphere in a dangerous time. The tearoom is a place of peace; the entrance to the room is tiny, so you can’t rush in with swords drawn. Weapons of war are to be left outside.”

“Another thing is the tea ceremony itself. As you know, when the guests receive their bowl of maccha tea, they are supposed to turn it before drinking. Let’s say the host is planning to poison the guest. He may apply some poison to the edge of the bowl and tell the guest to drink from it. By allowing the guest to turn the bowl, it gives him the freedom to choose from where to drink, at least symbolically; in most forms of the ceremony, one turns the bowl 45 degrees.”

“By the same token, the host must return half of the water he scoops from the kama (iron kettle) with the hishaku (bamboo water ladle) to transfer water to the bowl. He only empties half of the water from the hishaku into the bowl and returns the rest. This is another assurance that he will not poison the guest, as the host will drink the same water. The same goes for cleaning the chashaku bamboo tea scoop, which I feel is also connected to safety by demonstrating that there is nothing harmful or pointy on the scoop.” Shibata-sensei is probably thinking about something steeped in poison again. “I heard this from my teacher,” he adds, “an omotesenke master here in Gifu Prefecture.”

“Well, these are all my theories, but as I study Sado (the tea ceremony)—the word poison keeps popping up in my mind. It makes me think of many things about how the ceremony was performed in the troubling days of the long civil war in Japan.”

Shibata is making traditional tea utensils, but he also wants to try new things. “Take, for example, this golden chawan and this more plain-looking one,” he says. “Both were thrown on the same wheel and are made according to the same principles. I spin the wheel in a single state of mind.”

“Both bowls were thrown on the same wheel and are made according to the same principles. I spin the wheel in a single state of mind.”

“Time is an important element in this craft,” the potter says. “I was told once (and now he switches to the crude local dialect in Tajimi) ‘never spin the wheel too fast’. “At another time, I was told: ‘this bowl would have needed one more rotation.’ You may wonder what that means. I think the meaning is that with that one rotation, in that short instant, the bowl changes shape into something beautiful. That makes you feel a sense of flow in time. I think that feeling is part of the Minoware potter’s tradition.” All this is part of the story of pottery.

Another part of the Mino tradition, he explains, is rough clay. “What we call good clay does not mean good quality clay. In our neighbouring city, Seto, the clay is really high quality. You can make many good bowls in a day with that clay. It all goes very smoothly, but the clay here is rough, and however hard you try, the bowl will come out uneven and warped.

That connects to the underlying theme of the tea ceremony—the wabi-sabi—telling us that imperfection is beauty. “I go regularly to the US to teach pottery, and every time they ask about this mysterious wabi-sabi. I never seem to be able to explain. It’s hard to understand, even for the Japanese. This is quite different from China, where people love the beauty of symmetry. Perhaps it’s only us Japanese who like strangely bent, warped asymmetrical things.”

茶道具にふさわしく、歪みがあるけれど手に馴染む茶碗を考えて作っているのかと柴田さんに尋ねてみました。

「いや、考えてやってるわけではないんだけど、だいたい茶道に合うような形になるんです。 ちょうどよく歪んだ形になります。 考えてみれば、人間の手は曲がったものを作る方がうまくいくと思います。 手は色んなものにフィットし、ちょうど手に納まる部分を見つけることができるんだと思います」

I ask Shibata if he thinks about how to make these warped bowls so they fit well in the hand and work well in the tea ceremony. “No, not really, but a lot of the time they just come out as if they were made for Sado. They have just the right, warped shape. If you think about it, a human hand works better with bent things. The hand is flexible enough to find a comfortable grip.”

柴田さんは偶然出会った人からいただいたという贈り物を取り出しました。その人はガンで亡くなったそうですが、茶杓作りを趣味としていました。彼は細長く美しい茶杓を箱から出して見せてくれました。その箱には「心如水(心は水の如し)」と書かれています。 そしてこんな物語を話してくれました。

「これは竹で作られているんですよ。この形の茶杓を作るには、いい具合に曲がる竹が必要なんです。その人が亡くなる直前にプレゼントしてくれたこの茶杓は、私にとってとても大切なものとなりました。茶室にあるものすべてに物語があり、茶室はそういった物語を語るための空間なのです。この茶杓の持つストーリーはそれを示す良い例ですよね」

柴田さんはその美しく華奢な茶杓を箱にしまいながらこう締めくくりました。 「茶道の本質は物語だと思います。このような物語に満ちた部屋を作ることが、茶道の心であると私は考えています」

Shibata gets up to get a gift from a person he met coincidentally. The man passed away from cancer. His hobby was making chashaku. The potter slides the slender spoon out of its case and shows it. It’s a thing of beauty. It has a name written on it: Kokoro wa mizu no gotoshi —’The mind is like water’ . “This is made from bamboo,” Shibata explains. “You have to find one that bends exactly the way you need to make a spoon with this shape. This is a precious item to me. The man gave it to me as a present shortly before he passed away. It’s a fine example of how everything in the tearoom has a story, and the room is a space to tell those stories.”

Indeed, there is much depth in just those three characters written on the chashaku case. The man who wrote them is now gone. What made him choose this expression? Was he thinking about the end that was approaching? Did he wish to be like the water—calm, clear, and adaptable—to meet his final days?

Shibata-sensei slides the slender, beautiful spoon back into the case. “I think stories are the essence of the tea ceremony,” he says. “To create such a room full of stories is at the heart of the tea ceremony, in my view.”

白天目の物語

THE STORY OF THE SHIROTENMOKU

多治見は人口10万人程度の日本の地方都市です。ここにはその壮大さと美しさで知られる永保寺が建立されています。 このお寺は一説には、以前の記事で紹介した白天目茶碗の物語と関係があるという話があります。陶芸家であり、実験考古学研究者でもある青山双溪さんは、この貴重な茶碗の製造方法の解明と再現に長年力を注いできました。

「日本の仏教寺院は、茶道と禅の結びつきがあったため、昔から多くの茶道具を持っていました。永保寺は京都の臨川寺と関係がありますから、京都の僧侶たちが永保寺に茶道や洗練された茶道具を持ち込んだのかもしれませんね。中国の天目の写しを作る過程のどこかで、日本固有の形が生まれたのでしょう。白天目もきっと同じようにできたのだと思います。現在大名物と言われる白天目はここ小名田で作られたのです」

白天目と同じ焼物と思われる破片が発見された小名田の古窯で、日本の陶芸史におけるエキサイティングな伝統の痕跡が発掘されたそうです。その歴史は何世紀にも遡ることになります。

Tajimi is a small city in Japan with a population of 100,000. It is home to the Eihoji temple, which is known for its grandeur and beauty. The temple may be linked to the story of the Shiro tenmoku chawan, as I have written about in a previous article. Sokei Aoyama, a potter and experimental archaeologist who has dedicated years to reengineering the production method of these valuable teabowls, shared his theory with me.

“Buddhist temples in Japan possessed many tea utensils since there was a connection between the tea ceremony and Zen. I believe the tradition arrived at Onada by way of monks travelling between temples. As you know, we have a large and very important Zen temple in Tajimi, the Eihoji. Temples are part of a nationwide network. Eihoji is connected to the Rinsenji in Kyoto, so those Kyoto monks may have brought the tea ceremony and sophisticated tea utensils here. Somewhere in the process of producing a replica Chinese tenmoku, a native form was born. I believe the Shiro tenmoku must have come into existence this way, and that it happened in Onada.”

It seems like traces of an exciting tradition in Japanese pottery have been unearthed at the old kilns of Onada, where fragments of the Shiro tenmoku have been found. Their history goes back many centuries.

この天目碗について書いた以前の記事を引用してみましょう。

その白い茶碗は、近代日本の陶磁器に関する研究テーマの中で、議論と魅惑の対象となってきました。その茶碗は3点あり、かつては偉大な茶人、武野紹鴎(1502~1555年)によって所有されていました。紹鴎は16世紀の戦国時代に生きた人物です。

詳細はこちらをご覧ください。

To quote a previous article I wrote about these unique bowls:

“[The] white tea bowls have been the subject of debate and fascination throughout the discourse on Japanese pottery in the modern age. [Three] once belonged to the great tea master Takeno Jōō (1502–1555). Jōō lived during the Sengoku (warring states) period of the 16th century in Japan, a time of war and unrest.

紹鷗が所有していた茶碗のうち2点は、日本の文化史と政治史における偉人たちの手に渡っていきました。その中には、茶人の中の茶人である千利休もいました。その茶碗たちは、日本有数の武家で代々受け継がれていきます。そしてその中の一つは、青山さんの手仕事と、長い間忘れられていたこの美しい椀を作る技術を復活させようとする努力によって、現代に新たな命を吹き込まれた物語となりました。何年も試行錯誤を繰り返した末、青山さんは白天目が作られた時代の窯を再現する必要があることに気が付くのです。

Two of Jōō’s bowls would pass through the hands of some of the giants in Japan’s cultural and political history. Among them were Sen no Rikyū, a master among tea masters. The bowls were passed from generation to generation in some of Japan’s most powerful samurai clans. But this is also a story that took on a new life in our time through the work of Aoyama-sensei, and his efforts to bring back the long-forgotten technique to produce these beautiful bowls. After many years of trying, he realised that this would also require recreating a kiln from the heyday of the Shiro tenmoku.

澄心窯

THE CHOSHINGAMA KILN

「私はここ多治見の虎渓山の山の中に、古い時代の薪窯を再現し始めました。丘の斜面に長さ7.5メートル、高さ1メートルほどのトンネル状の大窯を作りたかったのです。灰釉を使っていた1500年頃の窯をイメージして設計しました。私の目標は、現存している大名物の白天目と同じものを焼くことでした。しかし1回目の焼成では、違う色に焼き上がり、思うような焼成結果にはなりませんでした」

“I started to recreate an early form of wood-firing kiln up in the mountains at Kokeizan here in Tajimi. I wanted to build an ōgama (literally “big kiln), 7,5 metres long and about 1 metre high—a tunnel in the slope of the hill. I wanted to design it in the image of a kiln from around 1500, a time when they used ash glaze. My goal was to fire Shiro tenmoku the same way the remaining bowls we have must have been fired. However, in the first firing, the pieces came out in the wrong style and colour.

青山さんは数十年かけ、500年もの間忘れ去られていた貴重な天目碗の製法を再現しようと努めてきました。その努力は多治見市や名古屋の徳川美術館にも認められましたが、青山さんはまだその成果に満足していません。現在徳川美術館には、彼が制作した白天目の写しのひとつが保管されており、また同美術館には現存する3点のうちの一つで、徳川家に伝来されてきたオリジナルの白天目も保管されています。これは武野紹鴎が最初に所有したものです。

「なぜここで白天目が作られたのか、どのような土が使われているのかを解明することに人生を費やしてきました」と青山さんは詳細について話し始めました。

「還元(焼成)と酸化(焼成)の効果を考えながら、窯の中の炎やガスの通り方を変えるために窯を直すことにしました。 3回目の窯焚きで、かなり良い還元焼成ができるようになり、自分のイメージに近づいたのですが、現存する長年使われた500年前のオリジナルとは見た目はまったく違っていました」

Aoyama-sensei has spent several decades trying to reengineer the production method of the precious bowls, which was forgotten for five hundred years. His efforts have been recognised by Tajimi City and the Tokugawa Art Museum in Nagoya, but he is still not completely satisfied with his achievements. One of the master’s reproductions is now kept by the Tokugawa Art Museum, which also keeps a couple of the few remaining original Shiro tenmoku. These are the ones first owned by Takeno Jōō.

“Takeno’s bowls were most certainly made here in Onada,’ says Aoyama-sensei, “and I have spent my life trying to figure out why this was the place of origin and what materials were used.”

“I set out to fix the kiln to change how the flame and gases would travel inside, thinking about the effects of reduction firing (kangen) and oxidation firing (sanka). By the third firing, I was able to achieve a pretty good reduction firing and came closer to what I wanted. But even so, the bowls looked totally different from those that had been in use for decades, and certainly the remaining originals from five hundred years ago.”

「元来の製法に忠実であったのに、何が問題だったのかと思うでしょう。答えは長い間使い込まないと、本来の白天目のようにならないんですよ」抹茶碗として使うことで、釉薬の細かいヒビ(貫入)に茶渋が入り込み、美しい模様に変化する、 また釉薬がかかっていない器の底の部分は、土の素材にお茶が染み込んで茶色く変色します。

I had stayed true to the original production method, so what was the problem? The answer is that you have to use the bowls over a long period of time before they start to look like the original Shiro tenmoku.” Tea residue creeps into the fine cracks in the glaze and turns them into a beautiful pattern. And the bottom part of the bowl, which is not covered with glaze, turns brown as tea seeps into the clay material.

「白天目はここで焼かれたに違いないのです!なぜなら、白天目を作るのに適した材料を含む土は、ここでしか手に入らないからです。釉薬の部分は還元焼成だと青みがかった色になり、酸化焼成だと黄色がかった色になります。粘土もその釉薬の色に影響します。粘土に含まれる鉄分が少なければ少ないほど、仕上がりは白くなります。白天目に使われた土はそういった性質のものです」

これらの天目碗は、かつて日本の上流階級が美的理想とした中国の伝統から脱却していることが分かります。よく見ると白天目は中国の陶磁器のシンメトリー(左右対称)とは異なり、形は完璧ではなく、確かに歪んでいます。

青山さんは深く茶道を研究しているわけではありませんが、自分の茶碗で抹茶を出すことを楽しんでいます。私の点て方を見たらどんな 茶人でも叱るだろうと彼は冗談を言います。フォーマルな点て方でなくともこの非常に珍しく貴重な茶碗でお抹茶をいただけるのは特別な気分になります。

ここ小名田には3つの古窯跡があり、白天目と同様の焼物とみられる破片が発見されています。 これらの窯は1400年代後半から1500年代中頃にかけて使われていました。「白天目は、戦国時代の織田信長やその後継者・豊臣秀吉、その息子・秀次などの著名人に愛されました。 残された3つの白天目のうち、1つは尾張徳川家、もう1つは加賀前田家が所蔵していたと記録されています。

“The shirotenmoku must have been fired here,” the master explains, “because only here can you find clay that contains the right materials for making these bowls, and fragments of such bowls have indeed been found here. If you use reduction firing, you will get bluish results, and with oxidation, you will get yellowish results. The clay also influences the colour. The less iron in the clay, the whiter the result. That is the kind of clay that was used for Shiro tenmoku.”

Taking a close look, you will see that the shapes of the Shiro Tenmoku are indeed not perfect but crooked. This contrasts with Chinese tradition, once viewed as the aesthetic ideal by the tea-drinking upper class in Japan.

While Aoyama-sensei is not actively studying Sado, he is happy to serve maccha in his tea bowls. He jokes that any tea master would scold him for his preparation method. Still, it is a special feeling to drink from these very rare and valuable bowls.

There are remains of three old kilns here in Onada village, where fragments of Shiro tenmoku have been discovered. The kilns were in use between the second half of the 1400s and the middle of the 1500s. “The Shiro tenmoku were regarded as perhaps the most brilliant and spectacular of all tea bowls in Japan and were loved by famous people, such as the mediaeval feudal lord Oda Nobunaga, his successor Toyotomi Hideyoshi, as well as his son Hidetsugu, both of whom were Kampaku (regents). Records show one of the remaining originals was later in possession by the daimyo house of Owari Tokugawa, and the other by the daimyo house of Kaga Maeda.

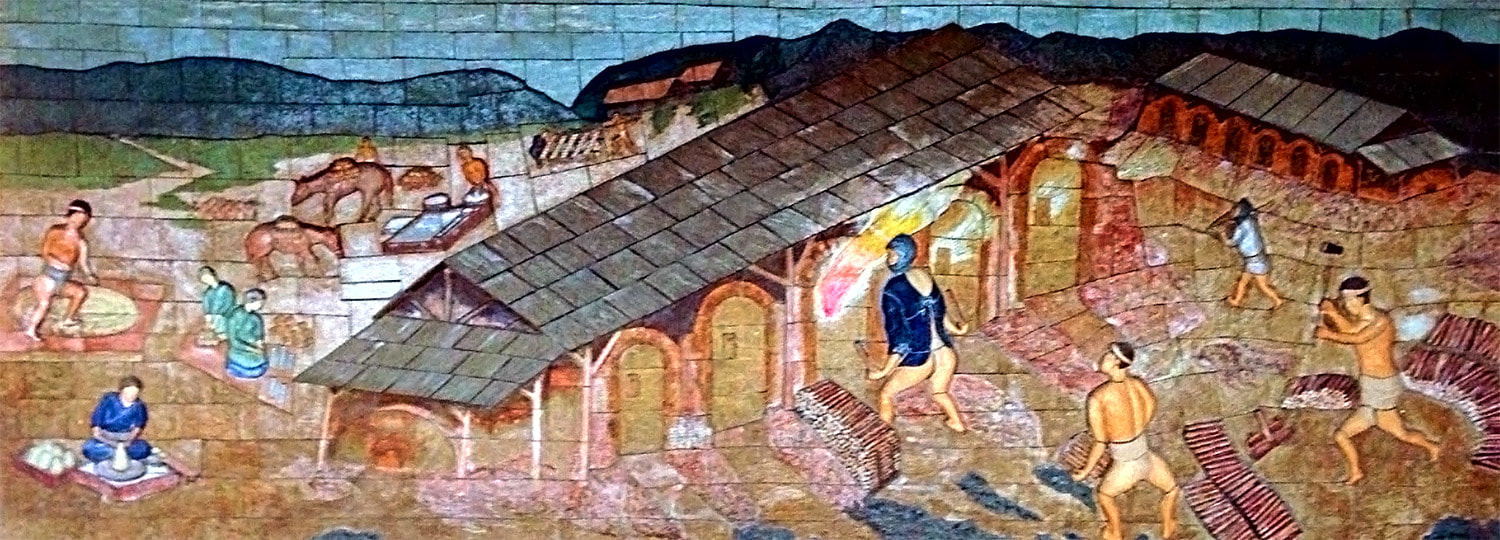

美しい抹茶碗を制作した職人たちの知られざる物語

THE UNTOLD STORY OF THE ORIGINAL CREATORS

歴史的な記録は、しばしば富裕層や有力者にスポットライトを当てがちで、少数の特権階級向けにこれらの素晴らしい作品を作るため、身を捧げた名もなき職人たちの血がにじむような努力はあまり語られません。しかし焼成中の澄心窯を見学してみると、職人たちが身をやつして従事した長時間に渡る肉体労働を深く理解することができるでしょう。

この体験を通して、冬の突き刺すような寒さと夏のうだるような暑さに耐えながら、古い時代の陶工たちが直面した過酷な労働条件について想像できるでしょう。現在まで伝わる大名物と言われる白天目なども当時の職人たちの努力の賜物であることを考えると、いっそう感慨深く鑑賞できることでしょう。

登り窯の詳細についてはこちらをご覧ください。

Historical records, quite often, tend to direct their spotlight towards the affluent and influential, overlooking the valiant efforts of the nameless craftsmen who dedicated themselves to producing these astonishing creations exclusively for the privileged few. However, by venturing to the Choshingama kiln during its firing, you shall gain a profound appreciation for the immense physical toil and extensive hours these artisans endured.

Through this experience, you will gain insight into the arduous working conditions that the ancient potters faced, braving the piercing chill of winter and the sweltering heat of summer. Each firing only yields a paltry few commendable pieces, if any at all, from a staggering assemblage numbering in the hundreds, having undergone days of meticulous firing. The surplus, unfortunately, succumbs to a fate of naught, underscoring the economic adversity confronting these artisans in times gone by.