多治見の中の陶器の町 PART 02 滝呂/笠原(日本語/English)

たじみDMO(一般社団法人 多治見市観光協会)では、合同会社Mimir(小名田町1-3-4)に委託し、多治見を紹介するコラム(Discover TAJIMI 英語版・日本語版)を執筆いただいています。今回のテーマは、多治見の中の陶器の町 PART 02 滝呂/笠原 のご紹介です。英訳の詳細はこちらをご覧ください。

前回の記事では多治見の陶器商人についてお話しました。(PART01はこちらから)

今回はその陶器商たちが取り扱っていた陶磁器の窯元の滝呂エリア、笠原エリアのお話です。

この2つの町はともに陶磁器産業で繁栄した町で、滝呂町はコーヒーカップなどの洋食器、笠原町はタイル生産で知られています。

In the previous piece, the focus was on the pottery merchants of Tajimi. This time the gaze turns upstream, to the kiln districts that once supplied those traders with their wares: the Takiro and Kasahara areas. Both towns flourished on the back of the ceramics industry; Takiro became known for Western-style tableware such as coffee cups, while Kasahara made its name in tile production.

この2つの町は多治見市の南西部に隣りあって位置し、多治見駅から南西方向に車で10分ほど進むとまず滝呂町、そのまま通り過ぎると笠原町にたどり着きます。

滝呂町と笠原町の境目辺りには古墳跡などが発掘されており、古い時代から人々の暮らしがあったようです。1600年前後に瀬戸から陶工が移り住み、滝呂に開窯したという言い伝えがありますが、発掘調査で見つかっている窯跡は中世鎌倉時代辺りに築かれたようで、それより前からこの地域に窯業があったことを伝えています。

These two settlements sit side by side in the south-west of Tajimi. From Tajimi Station, a ten–minute drive in the same direction brings one first to Takiro, and, if one continues along the road, on to Kasahara. Around the boundary between the two, archaeologists have unearthed the remains of ancient burial mounds, quiet evidence that people have lived here since long ago.

There is an old tale that potters came over from Seto around the year 1600 and opened kilns in Takiro. Yet excavations show kiln remains dating back to the medieval Kamakura period, suggesting that firing had already taken root in these hills even earlier.

.jpg)

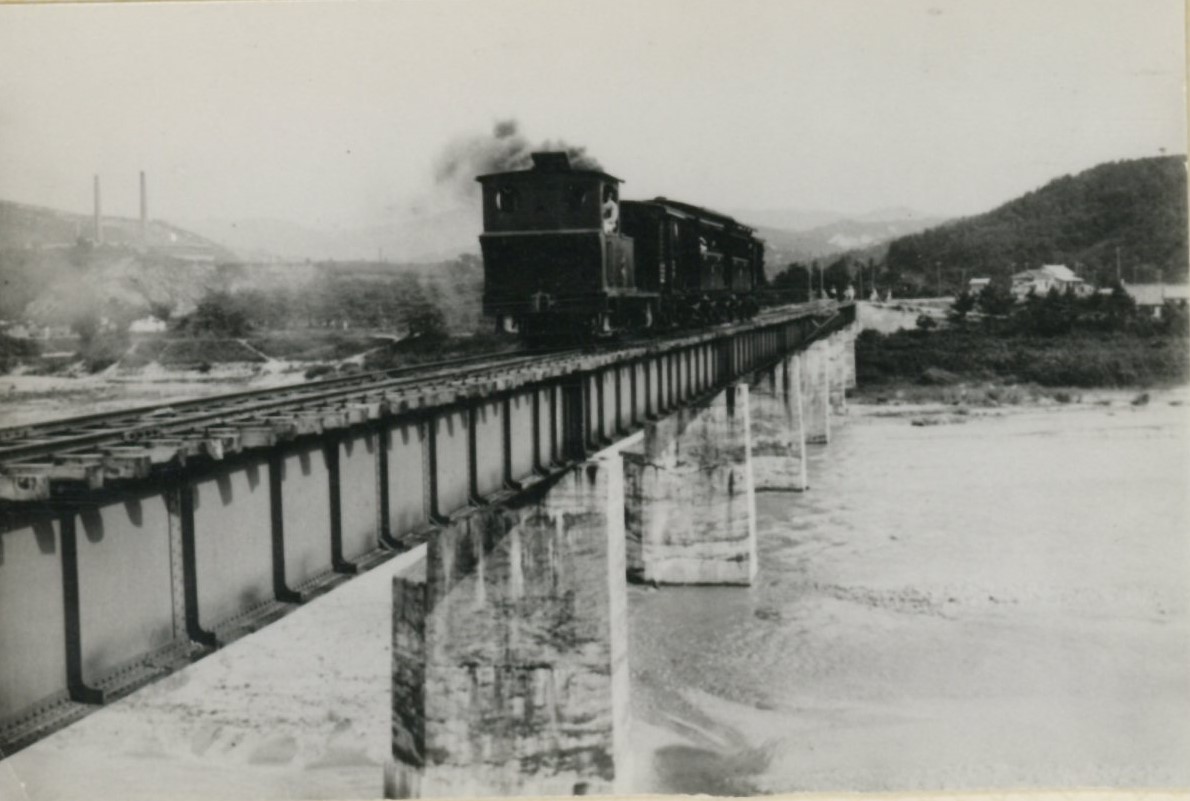

かつては多治見駅から笠原まで鉄道路線が敷かれ(笠原鉄道:1928年〜1978年)、蒸気機関車で大量の陶磁器製品が出荷されていました。現在は廃線となり「陶彩の径」と名付けられ、季節を感じられるウォーキングコースになっています。

この小さな町のための鉄道はその産業をますます発展させていきました。

ではこの2つの町がどのように窯業地として発展していったのでしょうか?

Once, a local railway ran from Tajimi Station out to Kasahara (the Kasahara Railway, 1928–1978), its steam locomotives hauling substantial quantities of ceramic ware away from this small valley.

Today, the line fell silent and was reborn as a footpath named “Tōsai no Michi,” a walking route where people can feel the changing seasons with each step.

For a modest country town, that little railway was a powerful artery, helping its industry to grow and spread far beyond the mountains that cradle it.

How then did these two towns come to take shape as kiln landscapes in their own right?

洋食器の町 滝呂 The tableware town – Takiro

江戸時代、地域の生産物に「親荷物」といった取り決めがあり、滝呂や笠原は「白錫」(灰釉徳利)と「あめ徳利」(飴釉徳利)と定められていました。

しかし江戸時代後期(19世紀初頭)になり、瀬戸で始まった磁器生産の技術が多治見にも伝わってきたのです。この時代、磁器製品はそれまで生産していた陶器より商品価値が高かったため、多治見の窯業各地に磁器製造の技術があっという間に広がったのは想像に難くありません。その中でも滝呂は磁器生産への移行が早かったようです。その上、滝呂は他に比べても技術力が高かったようで、窯跡から発掘された磁器製品からもその質の良さが見て取れます。

この時代に滝呂の神明神社には磁器の狛犬が奉納されており、滝呂の陶工たちが自分たちの技術力を誇りに思っていたことが感じられます。

In the Edo period there was a system known as “oyanimotsu” (親荷物) that allocated specific products to each locality, and Takiro and Kasahara were designated to produce “shiro-suzu” (ash-glazed sake flasks) and “ame-dokkuri” (amber-glazed flasks). In the late Edo period, at the dawn of the nineteenth century, the techniques for porcelain production that had begun in Seto reached Tajimi as well. Because porcelain commanded a higher value than the stoneware that had been made until then, it is not hard to imagine how swiftly porcelain technology spread through Tajimi’s kiln districts. Among them, Takiro seems to have shifted to porcelain particularly early. The town also appears to have stood out for its technical prowess, something that can be seen in the fine quality of the porcelain excavated from former kiln sites. In this period porcelain guardian dogs were dedicated to Takirō’s Shinmei Shrine, a quiet testament to how proud the potters of Takiro were of their own craft.

明治時代に入っても「親荷物」的な取り決めが続いていたようで、窯跡の発掘遺物から小皿が多く出ており、組合の専制権によって限定して小皿を生産していたと思われます。

このように順調に窯業地として成長していた滝呂地域ですが、明治30年代(1900年辺り)に国内向けの販売が不況になったことをきっかけに、輸出向けの洋食器生産へと転換をはかるのです。

そして洋食器の白磁を焼くのに適した石炭窯を多治見でもいち早く導入し、新しい時代の波に乗っていきました。

この輸出向けの洋食器生産は昭和30~40年代には最盛期を迎え、貨物列車でこの小さな町の駅から名古屋の貿易商まで大量に出荷されていたそうです。

Even after the Meiji era began in 1868, arrangements in the spirit of the old “oyanimotsu” system seem to have persisted, and excavations at former kiln sites have turned up many small plates, suggesting that the union’s exclusive rights kept production focused on these pieces. Thus Takiro continued to grow steadily as a kiln district, yet when the domestic market fell into recession around the late 1890s to early 1900s, the town pivoted towards Western-style tableware for export. It was among the first in Tajimi to introduce coal-fired kilns suited to firing white porcelain tableware, catching the swell of a new age. By the 1950s and 60s this export trade in Western tableware reached its height, with freight trains carrying large consignments from the little local station out to trading companies in Nagoya.

滝呂の町を歩いてみると、丘に沿って町が伸びていて、確かにこの地形は窯業が盛んになるわけだと納得させられます。

近代の石炭窯以降は斜面が必要ではありませんでしたが、この丘沿いに煙突がにょきにょきとそびえたって、滝呂の町のシンボルとなっていました。

現在は煙突も老朽化などでなくなりましたが、今でも先人の技術は受け継がれ洋食器の町として続いています。

Walking through Takiro, one notices how the town stretches along the hillside, and the shape of the land itself makes clear why kiln work once flourished here. After the arrival of modern coal-fired kilns, slopes were no longer a necessity, yet chimneys still rose in clusters along the ridge, becoming emblems of Takiro’s skyline. Those chimneys have since disappeared through age and decay, but the skills of earlier generations live on, and the town continues as a place of Western-style tableware.

.jpg)

そしてこのサイトの記事でも取り上げた長期作陶滞在施設Ho-Caもこの町にあります。

またその他に近々新しい作陶滞在施設ができる予定となっています。

This town is also home to Ho-Ca, the long-stay pottery residency featured elsewhere on this site. In addition, a new facility for residential pottery-making is due to open here before long.

タイルの町 笠原 The tile town – Kasahara

笠原町はかつて「笠原茶碗の町」として知られていましたが、今日ではモザイクタイルミュージアムがランドマークとなっているように、タイルの町として知られています。

笠原でも滝呂と同じく「親荷物」制度によって飯茶碗の生産が指定されていました。そのため明治時代までは茶碗を主に生産し、茶碗の町と呼ばれる程、窯業地として成長していきました。

しかしながらここ笠原にも国内の販売競争の激化、不況、災害、時代の変化などで新しい道を追求していかざるを得ない状況が訪れます。

Kasahara was once known as “the town of Kasahara tea bowls,” but today, with the Mosaic Tile Museum as its landmark, it is better understood as a town of tiles. Like Takiro, Kasahara was designated under the “oyanimotsu” system to produce rice bowls, and up to the Meiji era it mainly fired bowls, growing to the point where it was widely recognised as a town of tea bowls. In time, however, Kasahara too was forced to seek a new path, pressed by fiercer domestic competition, economic downturns, natural disasters, and the wider shifts of the age.

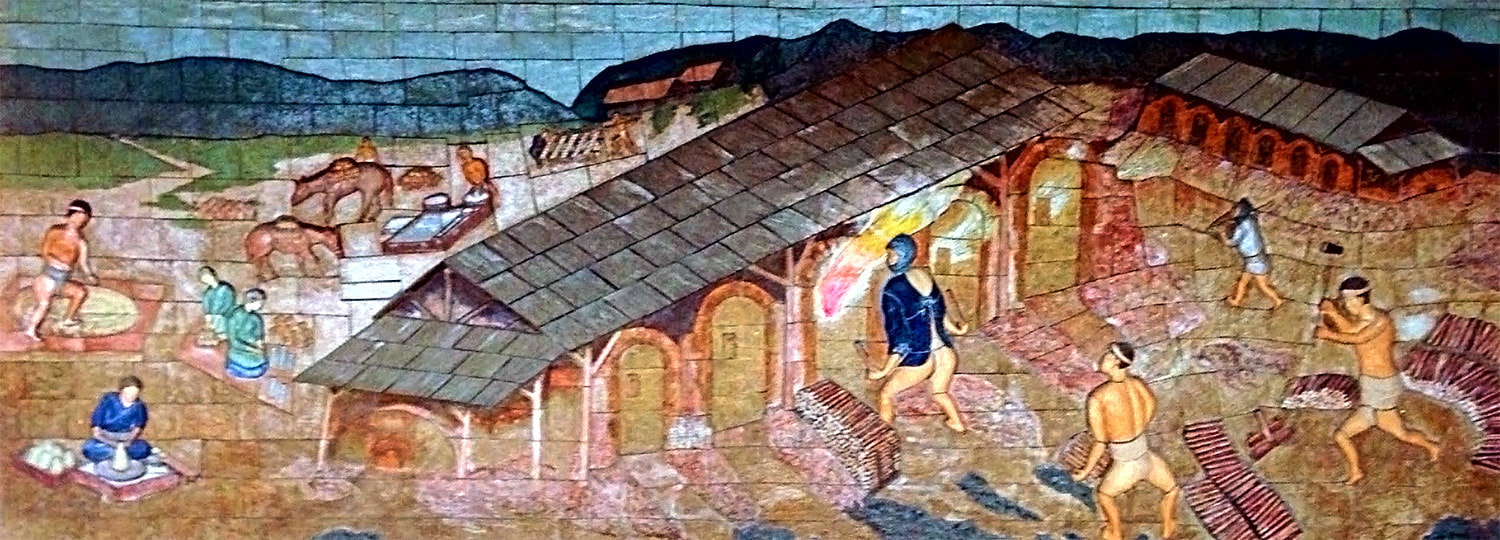

大正から昭和に時代が移り変わるころ、日本では関東大震災に見舞われ、建築も変革期を迎えていました。建物はより頑丈なコンクリート建築が多くなり、その装飾や衛生的理由のためタイルが様々な場所に使われるようになりました。日本でもその少し前から国内のタイル生産が少しずつ始まりだしていました。

多治見では1914年(大正3年)にタイルの生産が始まっています。驚くことにこの時はタイルという呼称はなく、「敷瓦」「壁瓦」「化粧煉瓦」「貼付煉瓦」などと呼ばれていたそうです。

As the years moved from Taishō into Shōwa, Japan was struck by the Great Kantō Earthquake and architecture entered a period of transformation. More and more buildings were made of reinforced concrete, and tiles began to be used in many places for ornament and for reasons of hygiene. In Japan, domestic tile production had tentatively begun a little earlier, and in Tajimi tile-making started in 1914, in the third year of Taishō, though at that time the word “tile” was not yet in use and they were called things like “floor bricks”, “wall bricks”, “decorative bricks”, or “applied bricks”.

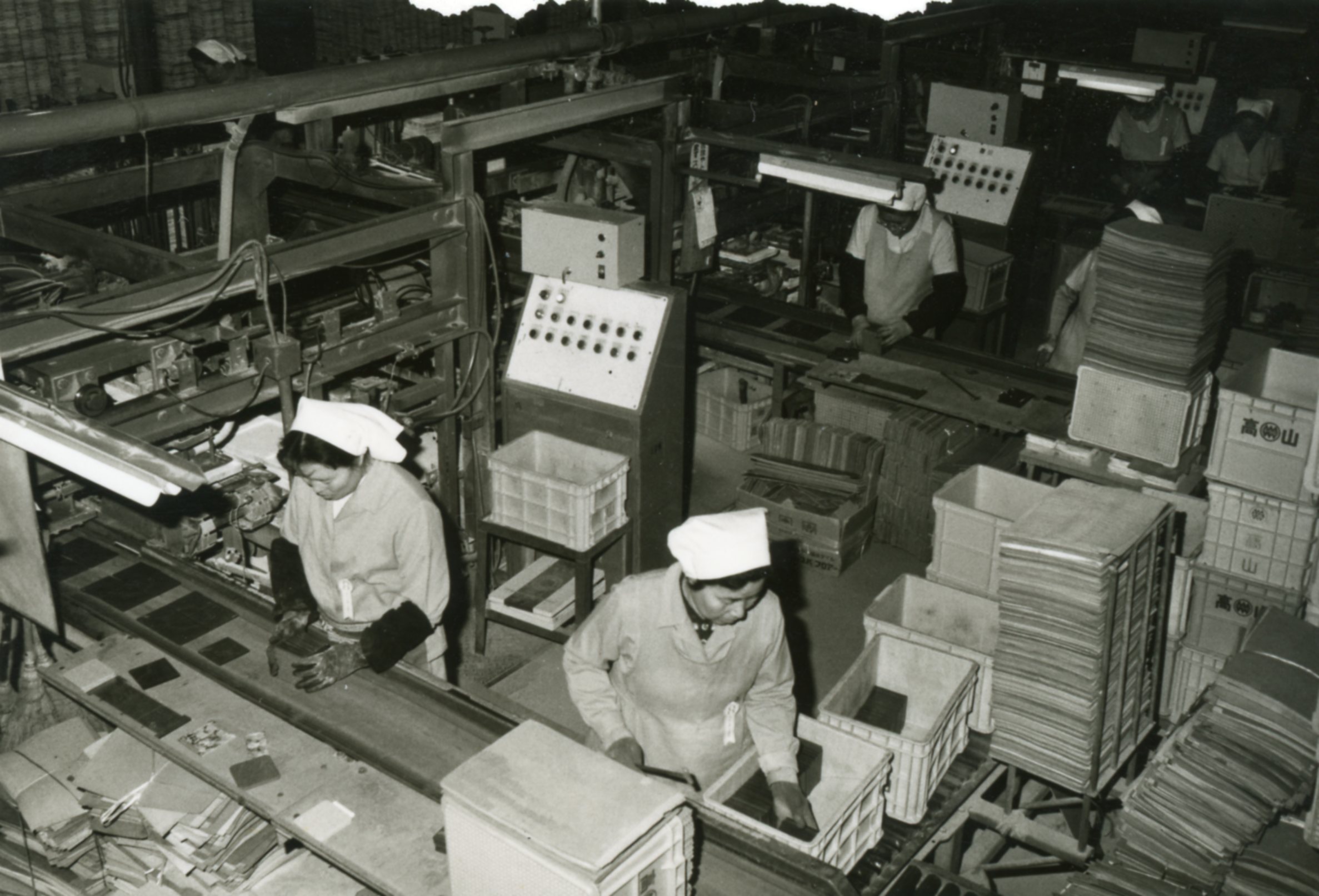

そんな中、笠原に生まれた山内逸三は、京都で陶磁と釉薬を学び、帰郷してタイル工場を設立します。当初、大型の建築用装飾タイルを中心に製造を始めました。しかし成形に時間もかかり、焼成中に割れてしまったりするので、もっと小さくシンプルなタイルができないかと数々の試行錯誤を経て1935年施釉磁器モザイクタイルの開発に成功。このモザイクタイルは表面積が50㎠以下の小型タイルで、均一なロットでの生産ができるため量産向きでした。このタイルは生産方法に革命を起こし、町中にタイル工場が次々と出来、戦後のタイル生産の中心地となったのです。

笠原で生産されたモザイクタイルは鉄道に乗せられてどんどん出荷され、1970年(昭和45年)の貨物輸送の最盛期に月間12,000トン、全国シェアの約8割を占め、名古屋港における主要な輸出品の一つとなっていました。

Amid these currents of change, a man named Yamauchi Itsuzō was born in Kasahara. He went to Kyoto to study ceramics and glazes, then returned home and founded a tile factory.

At first he focused on large decorative tiles for architecture, but the work was slow, the pieces prone to cracking in the kiln, and he began to wonder whether smaller, simpler tiles might be possible. After much trial and error, he succeeded in 1935 in developing glazed porcelain mosaic tiles.

These were small tiles with a surface area of less than 50 square centimetres, easy to produce in uniform batches and well suited to mass production. They revolutionised manufacturing methods, tile factories sprang up across the town, and Kasahara became a key centre of postwar tile production. The mosaic tiles made in Kasahara were loaded onto trains and shipped out in ever greater quantities. At the peak of freight transport in 1970, they reached 12,000 tonnes per month and accounted for around eighty percent of the national market, becoming one of the principal export goods handled at Nagoya Port.

.jpg)

-scaled.jpg)

現在モザイクタイルは町のアイデンティティとして町のあちこちで目にすることができます。中心にはモザイクタイルミュージアム、町の至る所にある数々のゴミステーションはモザイクタイルアートで飾られています。また、ミュージアム近くの和菓子店「陶勝軒」ではモザイクタイルをイメージしたお菓子がありますよ。

(ゴミステーションのモザイクタイルアートについての記事はこちらから)

Today mosaic tiles have become part of the town’s very identity, and you encounter them wherever you walk. At the centre stands the Mosaic Tile Museum, while garbage collection points throughout the town are adorned with mosaic tile art. Near the museum, the wagashi shop Tōshōken even sells sweets inspired by mosaic tiles. To learn more, read about The Mosaic Princess Tile Enthusiasts.

町歩きのヒント Hints for exploring the town on foot

- 陶彩の径(旧本多治見駅跡)

Tōsai no Michi, at the former Hon-Tajimi Station site.

Takiro Shinmei Shrine

Takiro Community Hall.

Takiro Central Park.

A residential pottery-making facility. HO-CA

Hanzōgama.

Mosaic Tile Museum Tajimi.

Kasahara Shinmeigū Shrine.

Tōshōken.